History of Pleasant Brook and Architecture

Official Pleasant Brook Site is here.

The history of Pleasant Brook begins with the development of the Peacock Farm neighborhood, so let’s start there.

More about Walter Pierce — and our interview with him — tagged here.

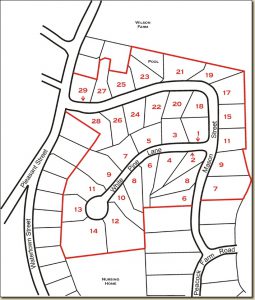

Original layout of Peacock Farm:

From the history section of our web site, Modernmass.com:

One of three important planned modernist developments, “Peacock Farm” was just a stone’s throw across Pleasant Street from the swimming pool of Six Moon Hill. This community was founded not by an architect associated with Harvard, as TAC was, but by Walter Pierce, from Harvard’s Cambridge rival, MIT. As Laurie Atwater began her article in Lexington’s Colonial Times newspaper,

The cover of the Sunday edition of the New York Times for September 13, 1959 announced: Russians Fire Rocket to the Moon, Expected to Hit Target Today….

Inside the pages, a story from “Lexington, Massachusetts: Colony of Contemporary Homes Will Be Repeated Near Boston.”

Pierce started his own architecture firm with Danforth Compton after studying at MIT with (among others) Carl Koch, a former student of Walter Gropius and a founding father of modern prefab housing in America. Koch was the founder of Techbuilt and Acorn Homes (a continuation of “kit” houses like the House by Mail Craftsman homes from Sears and Roebuck in the early-1900s). Compton and Pierce noticed a “for sale” sign near Route 2, Peacock Farm Road, a turn off of Watertown Street in Lexington. There was a 45-acre farm filled with wetlands, ledge, and woods. The two architects set out to become the developers of the site, with a plan they referred to as the “Program.” The concept was to build modern, aesthetically progressive homes that would be from a stock design yet looked as if they were custom built for the land.

After initially designing one-floor houses and building a handful of them, Compton suddenly and unexpectedly passed away and Pierce went on to design what is now known as the Peacock Farm House, a modern split-level home that, as Atwater notes in her article, “allowed the home to be ‘of the hill,” as Frank Lloyd Wright” espoused. The shape of this house style was flexible enough that it could adapt to flat or sloping lots. With some subtle variations, the typical Peacock Farm House had an entrance in the center of the broad side of the structure, a few steps up to a second floor consisting of three bedrooms and a bath or a bath and a half. There was the main floor with a kitchen, dining area and living room with a fireplace and exposed brick chimney. The structure was a basic post-and-beam system with few if any interior load-bearing walls, allowing for great flexibility in the floor plans, and many large windows unobstructed by sashes, mullions, or any unnecessary architectural features. A few steps to a lower level set in various depths of the grading of the site and sometimes a second lower level basement, depending on how much of a slope was present.

The Compton-Pierce team challenged the traditional notion of a house needing to be facing more or less square to the street. Free from this principle, they oriented the homes to be complimentary to the sites, taking advantage of the views and offering the sites the appearance of more space in between the houses. This was also counter to the trends of most modern developments, which seemed to operate from a scorched earth policy, clearing the land and plopping down cookie-cutter houses one after another and then possibly going back to plant saplings after the fact.

Many of these homes have been renovated and expanded over the years, much like those on Moon Hill and Five Fields. They seem very adaptable to such modifications. And most homeowners in these communities have adhered to the mild covenants that the original developers put into place to keep the communities aesthetically consistent. Note that I did not write, “homogeneous.” Modern, that is to say “present day” builders and developers should take note that a mish-mash neighborhood of new neo-colonial-Georgian-Victorians gussied up with various frills and flourishes is a less effective way of distinguishing a group of new houses from each other than the simple approach demonstrated by these forward-looking architects of the mid-century, using one or two plans and adapting them to the contours of the existing land with as little disturbance as possible to the existing conditions of the environment. Though these houses were not, as originally built, the most energy efficient by today’s standards, due to outdated heating systems, relatively little insulation, and large single-paned windows, they are easily retrofitted with updates for all of those components. They were, however, “green” from the get-go in their approach to land use, both in the conserving of the existing flora, with few having traditional lawns even today, minimizing impermeable surfaces (gravel driveways, e.g.), and reasonable lot sizes with larger amounts of common land for all to enjoy.

Which brings us to the socio-political philosophy that underlies these communities’ origins. Not only were these houses extraordinarily “new” in their styles, standing in stark contrast to the traditional New England vernacular via a contemporary European artistic aesthetic, but the founders of these developments also brought an egalitarian approach with attention to developing a community ideal that contrasted the largely politically and socially conservative post-war suburbs. One of the first large suburban development, Levittown, New York, was about conforming to the new neat and largely homogeneous suburban idea of the American Dream, trimmed lawns hemmed in by squared fences. These Lexington modernist developments tended to encourage responsibility and cooperation in the neighborhood as a whole, with partnerships in the non-profit corporations formed to watch over the common areas and the upholding of the benign covenants.

The layout of the communities allowed for a natural sort of privacy yet a community spirit was fostered and has continued to flourish in all of them. Peacock Farm celebrated its 60th anniversary in 2012. (See more about this and other modernist communities at www.Modernmass.com)

The developers that Walter Pierce had partnered with, Green and White, had great success with Peacock Farm and licensed Pierce’s design to develop other neighborhoods in town, including the land adjacent, which is now known as Pleasant Brook. As Pierce noted in our interview with him:

So was White a forward-thinking developer? Was it a risky thing at the time? Was he interested in modern homes specifically?

He had built a about six modern houses in Newton, and he lived in one of them. He was an economist by trade. Green was from a building background….

We were architects, real estate agents, and builder/developers all in one and we developed Peacock Farms up to Trotting Horse Drive. My partner died unexpectedly, in 1955. His family owned most of the stock and it was a question of whether or not to continue what Dan and I had started or get out of it. We had not been having great sales. But they wanted to stay in, as I had reassured them that we could do pretty well if we could get the price down. And about that time, Harmon White (a developer) came along and a contract was worked out with him. First he wanted a new design, which I did, the so-called “split-level house.” There was an earlier model, called the “A House.” There were only 7 of those. White had to sell and build on all the lots we had developed first, then he could develop the other roads for the rest of it. But all using my design. And it turned out to be so successful that, as you know, he, under my license went on to develop several other neighborhoods with the same house….

White had been so successful with Peacock Farm, he on his own, bought what was Shanahan Farm and developed that on his own, but again, with my license for the design of the house. But that’s a completely different neighborhood. We preserved eight acres of common land…. But what I am getting at is that he was enamored of the cache of Peacock Farm when at first he wanted his owners to be part of this pool. But we were at a point where we all had children and the pool was very crowded. We said we couldn’t do that. That’s when he set aside that lot for his own pool. And then (showing us maps), we had only developed Mason Street to a certain spot and then it dead ended….

Green and White, doing business as Benjamin Franklin Homes, built the homes on Mason and White Pine, and built a new pool, which is actually overseen under a separate corporation, so it is fully optional. New homeowners can opt to buy a share in the pool and pay a nominal fee seasonally, or pay a higher amount seasonally without owning shares.

From the Lexington historic survey of Pleasant Brook:

With the Peacock Farm house having been in construction since 1955, the homes built in Pleasant Brook from 1967 to 1970 were able to incorporate improvements to the original design, including a roughly 625 square foot full-height poured basement under the middle level of the house, instead of the crawlspace used in the original design. Additionally, the middle level living area of most of the homes is 3 feet longer measuring 26′ by 51′ in plan, as opposed to a total length of 48′ in the original design. The house design allowed for mirror-image versions of the plan, which enabled each house to be tailored to the siting and orientation on each lot, including the entrance to the house through a foyer on the lower level or on the middle level depending on the site characteristics. The two most common orientations of the house relative to the street are the broad side parallel with the street or the end of the house containing the upper and lower levels facing the street. The houses utilize a combination of wood and steel post-and-beam construction techniques, which allowed for large bands of windows and flexibility for interior room layouts with most internal walls non load-bearing. The structures have a shallow-pitched, asymmetric gable roof with one slope longer than the other, and broadly overhanging eaves which display five carrying wood beams that are exposed along the broadsides of the house. The homes contained roughly 40 to 50 windows of single-pane glass, arranged in multiple bands of casement and fixed window-sets, including trapezoidal clerestory windows tucked under the eaves of one side of the middle level of the house. The exteriors were originally finished in a stained vertical tongue-and-groove cedar siding; plywood window bands insets; steel window-sets with no casings or aprons; and plain painted doors.

Green and White went on to develop other neighborhoods in Lexington, including Shaker Glen/Glen Estates, Rumford Road, The Grove, and Upper Turning Mill.

More about Walter Pierce — and our interview with him — tagged here. See everything about Peacock Farm homes and neighborhoods here.