Some years back, the architect and Lexington resident, Walter Pierce was quoted in the Boston Globe, describing Peacock Farm, a pioneering modernist neighborhood in Lexington that he developed with partner, Danforth Compton. Mr. Pierce told the Globe, ““we were taught that architecture could contribute to social policy; we were zealous and were reacting against the conventional architecture up to that time.” (You can read more about the history of the neighborhood at our post here.)

I was interested in hearing more about that tension between conventional tradition in the region and the progressive steps they were trying to take, as well as in hearing Mr. Pierce’s feelings about the legacy of his architecture, his concepts of a neighborhood, and how they are relevant today. Are the homes of Moon Hill, Peacock Farm, Five Fields, Snake Hill, and other neighborhoods of the era to be considered “modern” after 60+ years, or if there should be some new definition of the word? Is “modernism” a style as well as a philosophy? Does “midcentury modernism” now itself a similar sort of nostalgia manifested in the neo-traditionalism of new Colonials and Victorians?

My business partner, John Tse, and I have listed and sold five or six houses in Peacock Farm in the past few years. The recent turnover of many houses in the neighborhood after decades of stability was a bit of a novelty. Until recently, the houses have remained in the hands of the original owners in many cases. Such turnover offers a mixed bag. There can be tensions over new owners adhering to longstanding covenants, as well as a welcome resurgence in appreciation of the style of home and ethos represented in the Peacock Farm neighborhood concept.

We sat down for an interview with Walter Pierce last week. Reading my typically long-winded email of discussion points, he put this neophyte right in his place!

“Like many who are interested in the era, you know a little, but…” he started.

“But not enough, right?” I asked. “Just enough to be dangerous”

Thankfully, he laughed. Here is roughly how the discussion went.

*******

Bill Janovitz: Dan Compton was your partner initially. How many had you built yourselves, before White and Green, the developers, step in as partners?

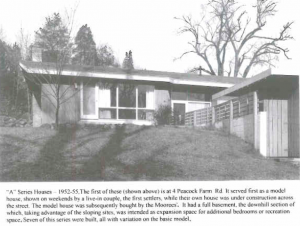

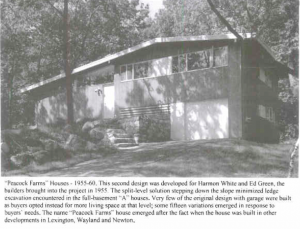

Walter Pierce: We were architects, real estate agents, and builder/developers all in one and we developed Peacock Farms up to Trotting Horse Drive. My partner died unexpectedly, in 1955. His family owned most of the stock and it was a question of whether or not to continue what Dan and I had started or get out of it. We had not been having great sales. But they wanted to stay in, as I had reassured them that we could do pretty well if we could get the price down. And about that time, Harmon White (a developer) came along and a contract was worked out with him. First he wanted a new design, which I did, the so-called “split-level house.” There was an earlier model, called the “A House.” There were only 7 of those. White had to sell and build on all the lots we had developed first, then he could develop the other roads for the rest of it. But all using my design. And it turned out to be so successful that, as you know, he, under my license went on to develop several other neighborhoods with the same house.

Original “A” Series House.

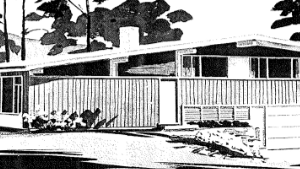

Original split-level “Peacock Farm” House. (Images from “Peacock Farm: 1952-2002,” a commemorative neighborhood booklet)

Original split-level “Peacock Farm” House. (Images from “Peacock Farm: 1952-2002,” a commemorative neighborhood booklet)

So was White a forward-thinking developer? Was it a risky thing at the time? Was he interested in modern homes specifically?

He had built a about six modern houses in Newton, and he lived in one of them. He was an economist by trade. Green was from a building background.

Carl Koch predated the Peacock Farm and Six Moon Hill neighborhoods with his Snake Hill development in Belmont, building a post-and-beam, sort of International style…

Well, already you’re using the wrong terms. None of this is International Style. Post and beam has nothing to do with it either.

OK, Correct me! (laughs)

I will! You know, having read this (he picks up a print out of an email outline of my discussion points), if you’ll excuse me if I make a comment on that, and having talked to a lot of people about these things, they’re partially informed about the modern homes.

Yeah, that’s me: just partially informed!

In terms of American modern houses, there were two strains, one came out of Europe and got dubbed the “International Style.” I think Philip Johnson might have coined that term. The other strain is almost purely American and came out of the West Coast, Washington, Oregon, California. And largely under the dominance of William Wurster who became Dean at MIT and went back to become that Dean Of Berkley, and the California, American style took root here. And in fact the two schools are quite different. Harvard GSD’s (Graduate School of Design), thanks to (Walter) Gropius, who turned Harvard around, it was a European-based, International style, kind of ideological format. The American brand of modern, a lot of people have declared it to be more “humanistic,” more laid-back and informal, not so doctrinaire — and that’s a real distinction. And the affinity with Europe and the American version of modern architecture, which took root at MIT, the European connection there is Scandinavian. Alvar Aalto was a guest lecturer at MIT and he designed Baker House.

Yes, and a lot of furniture that was used at MIT as well…

Yes, I have some of his furniture here (here gestures). So I right away make that distinction. So keep that in mind, whoever you talk to.

Yes, so let me clarify: So you’re saying the strain that came through Gropius and subsequently through the GSD was primarily German, of the Bauhaus, specifically…

Yes.

…from Dessau. And your strain, which was what influenced you, is primarily American, with a Scandinavian influence as well. So, there is an affinity between Scandinavians and the West Coast of the US. Do you think the West Coast also had a Japanese influence, via (Frank Lloyd) Wright or otherwise?

Everybody had a Japanese influence, including Wright. Of course, if you want to talk about modern architecture, there’s the supreme god, Wright, off by himself. You can’t categorize him. But all of us, all of us including the Europeans, learned from Wright. He did a marvelous set of houses around Chicago — Oak Park…So he is a law unto himself. And he influenced everybody — indirectly. He never had a very good school. He never became prominent in one of the established schools but his presence in the world is so great, that he influenced everybody.

So speaking of the West Coast and how it took root there, all the way down the Coast, and it’s still a very popular style, and when I say “style,” I mean modern in a general sense.

Well, the West Coast has always been one step ahead of the rest of the country in new developments, whether green movements, architecture, on and on.

Well, why do you feel this modernist style, for lack of a better term…

Don’t call it a style. There’s got to be a better term. For practicing architects, it should not be about a style; it’s a way of thinking — rational way of approaching the design of a house.

Yes, and it manifested itself, in this area, there are certain traits, an open floor plan, tends to be more flow, and economy of space, more use of glass…

Yes, all of that. It was accommodating the way modern American families were beginning to live. But the kiss of death was the Chicago World’s Fair of the 1870s. And a bunch of Eastern architects were invited to design all of the Fair buildings. And they are all in neo-classic style.

What about Louis Sullivan, didn’t he…?

No! Come on! Sullivan was midwestern! They overwhelmed this budding American vernacular. Sullivan had one building at the Fair.

Yes, but I am not articulating my question well. On the West Coast, there was a continuation of this tradition with those traits we mentioned, use of glass and so on. I guess more to contrast with the Boston area, where we had this era of progress, I think of it as progress anyway, in the 1950s, in Lexington alone with Peacock Farm and the two TAC (The Architects Collaborative) developments (Six Moon Hill and Five Fields), but then it seemed to stop after the subsequent developments.

I’ll give you another statistic: 98% of the houses built in this country are not designed by architects. They are built by developers and a house in that category is a consumer good like soap or toothpaste. There’s no owner on site when these houses are designed. It’s developers looking at what they consider the market. And they build what they think the market wants. And back to the Chicago World’s Fair, which introduced the sort of neo-classicism, the Colonial house came roaring back as a style. And it’s never left.

Yes, so you had all of these Colonial Revivals at the turn of the century.

Exactly. And the indigenous American style that was being designed by Wright and Sullivan and the great Chicago architects, was overwhelmed by this stuff. California had a lot of things going for it, in addition from being far away from European influence. It had a benign climate, don’t have to worry about freezing and thawing or lots of insulation. They had lots of single-pane glass. There was also a more modern-thinking population and some of the developers out there were building modern houses.

So after that, into the 1960s, you were building, or your design was still being used.

Well, back to that 98%, I think we had satisfied the market here. You don’t see any more.

That’s what I am asking. Do you think that there was a specific point where the developers found that they could not sell any more?

Well, they didn’t do anymore. The developers didn’t do any of these.

But why?

The architect-based developments built these houses. No regular developer that I know has developed a modern-house development.

Around here.

Right, in California, a different story.

So why do you think developers balked? Why did everyone feel the market was satisfied or saturated. Wouldn’t a developer see these as successful?

You’d have to ask a developer that one.

Ha, yes, we do so, often!

It comes back to the house as a piece of consumer goods.

Yes, we find that as real estate agents that to try to get a builder… well, nowadays mostly around here, as you know, it’s tear-downs and one-off houses. There is very little land left for developments. And very few take on s single modernist spec house on a tear-down lot.

Well, look at that big color magazine you put out. Is it Hammond Real Estate?

Yes, that’s our company.

Well, there are almost no modern houses in there. There’s your market!

Except our listings! We love to market them. And in fact, the one on the current cover is a modern house in Weston for over $3 million.

I guess I did see that, right.

So I think you’ll still see these individual commissions, right?

Well, there’s always been a very tiny market for affluent, well-educated clients for custom homes. I did a lot of those.

So that leads me to my next question, so you did some more of those in Lincoln, in Brown’s Wood. What else did you do after those?

I did two big houses up on the coast, NH, I did a house in AZ in the desert, some houses in this area. Custom houses. Custom houses.

Were you part of a firm, a partnership, or on your own?

I was on my own for five years after my partner died but I came together with another partner and we moved out of houses altogether, because you can’t make a living designing houses. But my firm was Peirce, Pierce, and Kramer.

So you went on to do institutional commissions.

Right, schools, laboratories, universities. UMass Engineering, Wood’s Hole, Jackson-Mann school in Boston.

(We get back to the discussion about the end of modernist developments, clients who want a modern house and so on.)

But to find a piece of land, take it through a planning board, design a house for a vague undefined market, a developer, he’s got to look around and see what’s being sold. Like soap.

You had said something interesting, though, You felt you had sold through the market and there were no other buyers for these houses, or there were enough to turn over for new buyers.

Well White went on with this house and did three or four other developments (Shaker Glenn; Turning Mill; the Grove; Rumford Road area). And then I think he just got tired of doing it. He was getting older, and he retired. But I don’t see anyone stepping into his shoes, or mine.

Well, part of it is land development.

And if you want to put another point on it, this country is very conservative. That’s what we call the buying public. Verrry conservative.

We find that there are few developers who even would want to build this if they could find a market.

They’re probably living in a big garrison Colonial. McMansion.

(Side note: there are signs of smaller, well-designed, environmentally friendly developments, priced reasonably, catching on in this area. Though, not “modernist,” see Riverwalk in West Concord.)

Your house was probably the most singular in this neighborhood.

Well I did three or four custom houses in Peacock Farm. Each individual. And then I have done some very large additions to the standard houses. About half a dozen, that are bigger than the original houses.

And you’re still head of the design committee, the Architectural Guidelines?

Oh yes, you’re talking about our association now. We’re reorganizing it a bit and I’m glad I’m no longer the only architect living here. There are several living here who I have roped in to take my place as reviewers. (I mention some I know) The Dean of Architecture at Northeastern is living in one of the “standard” houses.

The split-level style was requested by White?

No. His program turned out to be the same we had started with. Three bedrooms, one-and-a-half baths, priced for a young family, with an expansion lower level. Because of this site, we ran into a lot of ledge. And this was designed to step down the hill

And with the split-level, you could spin it around according to the hill orientation.

Exactly.

But you were already thinking that way.

White had no ideas about the houses themselves He just had the needs. One of which was a garage. Which was on the lower level. But right away we found out that the buyers didn’t want a garage; they wanted the expansion space. There aren’t many of those. After the model, he used a buyer’s mortgage to build a house. He didn’t put up his own money. It was the buyers’ construction mortgage that provided the cash flow.

So they weren’t custom builds per se, but the ended up being partners in the financing of the houses.

They were custom laid-out in terms of interiors.

I guess one question I always had was, did you feel an affinity with or that you were on a similar mission as the TAC people?

Oh yes, we were all imbued with the idea of the modern house and we were all doing custom houses and simultaneously liked the challenge we made for ourselves: can we design a standard house at a price that young home owners could afford and that meant standardization.

Was there a real resistance to what you were doing in town?

Yes.

I have read anecdotal things about trying to get financing and such. Was there anything hostile?

Not really. We had to go through the planning board. And they had nothing to say, finally about the style of house. But they would mutter about them looking like “chicken coops” (Smiling).

Yeah I have heard that one (laughing). But the clientele were academics, engineers, professionals….

Yes, from the two big schools. That’s a real distinction you could make. That these were people with advance degrees, all professionals.

And all young.

Yes, young.

With an optimism about the future.

Well, I think we all had that, coming out of the War. We were all optimistic. And naive.

I know there was some real care taken about the terrain, and siting the houses whenever possible with exposure in mind, how the extended eaves overhang and so on.

Well, we sited each house individually. And when White came in, it was nice when he took over the sales, he dealt with the buyers. He and they would visit the site, look at the site, the slope and approximate how the house might sit on the site, Then I would come out and fine tune it further and stake it and do a site plan and then they could proceed.

Aside from the siting of it, I assume energy efficiency was no as much a consideration as it is now.

Not at all.

But there were some passive elements you took into consideration, yes?

Well, we go back to California. When I was doing my thesis, I became very enamored of what California was doing with schools. And again, with that California climate, they were designing schools with through-ventilation in the classrooms and overhangs to block the sun. With the standard house, we didn’t have as much of an option because we had the standard design. So the house and the site didn’t always match up to take advantage of the site. But here (the Pierce House), you are facing sort of southwest, the overhang is about four-and-a-half feet. It is calculated to block the sun in the summer, which it is doing right now. And in the winter, the sun actually hits the back wall. The thermostat doesn’t come on for a while. Although, we were not very good with insulation. The roofs are fairly well insulated, but not the walls.

But compared to the houses that were being built at the time, it was what was available. And the glass?

Well the maxim on the glass, word of mouth in the fraternity was, you never maximize the cost of insulating the glass though any savings in oil, because oil was so cheap. So they were all single-pane. I have since replaced mine. The steel-sash have storms, but I replaced the big panes.

The steel are Hope windows?

Yes.

We haven’t really talked about the covenants. As far as they go, the creation and enforcement of them – can we speak about that? I know you wanted to maintain a certain consistency.

Exactly.

But do feel tension has waxed and wained over the covenants?

Some tension has emerged recently for reasons I don’t understand. We have the right law with teeth it, because there was a master deed on the farmland when we bought it, we slapped a deed restriction on the whole thing and that flows to every house lot. And we have an elected board of directors and we have architectural controls And every once in a while we get a case where people sort of thumb their nose at the thing and everyone gets up in arms. We are more interested in neighborhood harmony than putting up obstacles.

And when you put these into place, which seems to me a very forward-thinking thing, was it a common thing? Were their precedents, maybe with other developments, not Moon Hill.

I don’t think they did it up there. One of them did but I think it expired.

Five Fields, maybe.

Maybe, but they don’t have it now. We were alert. We renewed ours, because state law said that if you didn’t renew it after 50 years, it expired, period.

The Globe ran an article about the idea of preserving these a few years back that addressed covenants and neighborhood harmony in Moon Hill and it addressed the so-called Big Dig House, which pretty much fits in with the philosophy, if you ask me.

Yes.

But it did discuss whether covenants were enforceable from the get-go. Did Carl Koch have them in place in Snake Hill?

Ezra Stoller Shot of a Snake Hill House

That’s a good question. No, I don’t think he did. Because someone just told me they are tearing some down now.

I had not heard that. I had heard about the cause celebre of the house at Belmont Hill School that they tore down a few years ago. (Eleanor Raymond, Rachael Raymond House)

That was one of the first solar houses. It was the Belmont Hill School that tore it down,.

I heard, That’s a shame. And how do you feel about that, the preservation efforts for this period of architecture. (We discuss a recent New York Times article about an exhibit by Rem Koolhaus regarding urban preservation) But just about these houses. I heard there is a movement afoot to get them on the National Registry of Historic Houses.

That’s in the works. I think it’s fine. We’re very happy. Of the five developments in Lexington, they picked us to go first for the nomination because they felt there is more cohesion here, there was the architectural restraint and this had more of a chance of going through the process than the others. I think that there was a lot of enthusiasm here.

Do you feel that it makes them museum pieces in a way? Does it ossify the houses as a sort of style? Do they need protection?

Well, you can add on to these. As long as you are in the same style. You can tell me better than I could, but I have heard of no nibble from a developer about land here.

No, not here, but it happened in Turning Mill (a Peacock Farm-style house was torn down about a dozen years ago and a new shingle style built in its place).

There you go, because they don’t have the restraints. I think our deed restrictions have a lot to do with keeping them away.

Well, let’s play this out, though, just as an exercise. If someone wanted to tear one down and build in the, quote, same style, end quote, and you were saying there is no real style, it was, rather, a rational way of thinking, well then how or what’s going to meet that criteria in a hypothetical way, does it stay true to an era.

It has to go through the board of directors.

So it becomes a completely subjective thing of what the style is, right?

Stop using he word “style.”

That’s what I am saying though (laughing). You used the word “style.”

You infected me. (laughs)

But that’s the point, I think. So if someone wanted to tear it down and build something, I guess we know it when we see it, eh?

Right. I hope you haven’t got one of these people in your back pocket!

No! You know me. I want to see them preserved.

I think we look for the same use of materials, use of glass, same siting, no clear-cutting of woods. I would come down hard on deviations from that.

Right, so it is more the philosophy than anything.

Well, and the look, too.

John Tse: We were talking about his house: Four-and-a-half foot overhang, the southwest side has all windows…

Well we were dealing with where the trees were, and privacy, and so we were juggling. One of the advantages of this, this is a square house. Its built on a six-by-six module in both directions, which is the Hope windows module. Those are six feet wide. So by the time we got through with siting the house, with a stairway in the middle, due south is on the diagonal of the square. And it turns out to be a very good orientation because we get sun southeast and sun southwest, even in the winter. Whereas if it had faced due south, we would have lost the sun by noon and by three in the afternoon. And one of the nice things of the center stairway is you come in from below, you come up in the middle you can get to everything without any corridors.

JT: That’s one of the best things I have enjoyed about the houses you designed, there are really no hallways, no wasted space, everything is being used.

Well, you’ve been to most of these houses, in fact, you’ve sold most of them.

BJ: But here, I think the biggest testament to how well these houses work is how long people stayed in them. A whole generation.

Right.

And it’s a very transient area.

Well, as you know, they come on the market for a very short time.

Yes.

But here are these, a lot of custom additions to the standard house.

Its interesting to me that people think of Mason Street as Peacock Farm but it is part of the Pleasant Brook Association. Was that because all the deeds were split up and the common land shares divided already?

White had been so successful with Peacock Farm, he on his own, bought what was Shanahan Farm and developed that on his own, but again, with my license for the design of the house. But that’s a completely different neighborhood. We preserved eight acres of common land. And that was before there was a wetlands law. Today we could not have done anything else with it. But he only set aside one 15,000-square-foot lot for the swimming pool. But what I am getting at is that he was enamored of the cache of Peacock Farm when at first he wanted his owners to be part of this pool. But we were at a point where we all had children and the pool was very crowded. We said we couldn’t do that. That’s when he set aside that lot for his own pool. And then (showing us maps), we had only developed Mason Street to a certain spot and then it dead ended. But he shoehorned in some lots to fit them into the Peacock Farm master site. They with White at their elbow, several of them joined the other pool when they could have joined our pool — maybe they didn’t know that — because they were in the original lot. And they still could. (He laughs looking at the triangle lots.) I think it ought to be against the law to develop a lot like that!

Peacock Farm site plan with Pleasant Brook to northwest

Are they also therefore subject to the architectural guidelines.

Oh sure. If they’re in they’re in.

______________________

An end note:

In my research, I came across a letter from Mr. Pierce to the Editor of Harvard Magazine regarding the Carpenter Center at Harvard, the only building in North America designed by noted Swiss architect, Le Corbusier:

JOAN WICKERSHAM uses as a measure of architectural excellence at Harvard and other area colleges the Harleston Parker Medal awarded annually by the Boston Society of Architects, and ponders why Harvard, by this measure, hasn’t fared better. Since she evaluates only the years 2000 and later, the Carpenter Center does not come up. The selection of Le Corbusier as the architect for the center was one of the most significant in Harvard’s history and one of the most controversial: In 1963 I chaired the Harleston Parker Committee which chose the Carpenter Center for the award…only to have our selection overturned by the BSA membership voting in its annual meeting, the first time in the medal’s long history that that had happened. The following year a new committee again selected the Carpenter Center for the award. And this time it passed…a sort of redemption for everyone.

I brought this up with Mr. Pierce.

WP: They were the blue bloods of Boston and after a few martinis, they sat down and we had to present a big picture of our choice and tell them why we picked it. And they voted it down! The only time the board and the membership had to approve the committee’s selection and they voted it down! The history of the medal goes back to 1875. the only time in history it got voted down.

The next day Time and Newsweek and the Globe were on the phone with me talking about “bluenose Boston” and on and on! And then you can fast forward to 2007 maybe when Joan Wickersham from Architect Boston wrote an article, how come Harvard doesn’t have any Harleston Parker medalswhereas MIT does, sticking it to Harvard. And I wrote her a note saying, Harvard had a chance. The next year there was a Harleston Parker committee, all new members and chairman. They came up with the Carpenter Center again and it was approved, because I got the rules changed. I said this was ridiculous for the young committee of seven members to go before the membership. We can’t fiddle with the original grant, which was given a man named Harleston Parker. But we could change the approval process. Don’t have the chairman of the committee hung out to dry. Have the board of directors approve the committee’s choice. So the next year the board of directors, which is an elected board of 12, good guys, so we took it to the Board. They approved it. They went before the membership with not only the committee, but the board’s approval. And it passed. So wrote Architecture Boston and said Harvard finally did get a building approved. But you didn’t take your search back far enough. She thought my letter was good enough to put into the Harvard Magazine.

Interview crossposted at Boston Magazine dot com.