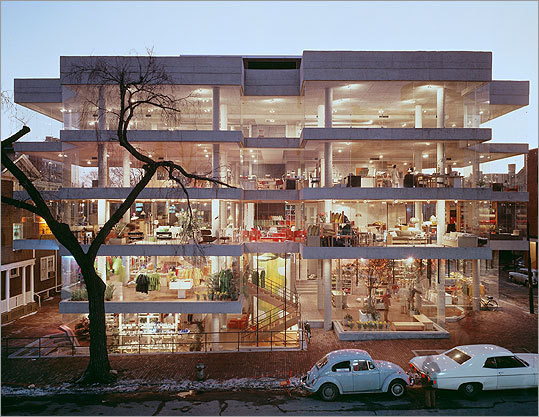

In 2015 I attended a talk given by a couple of the authors of Heroic: Concrete Architecture and the New Boston, which had just been published. The insight of the authors was so keen and their presentation so impressive that I naturally purchased a copy at the event. It is truly a hefty tome, more like a high quality textbook than an art/architecture-sort of book. But in addition to incisive essays and interviews, its heavy paper is filled with high quality images, including a two-page reproduction of this favorite shot of the Design Research Center on Brattle Street in Harvard Square, Cambridge, taken by Ezra Stoller, whose work can be seen throughout our posts on Six Moon Hill, Five Fields, and Snake Hill. [Neighborhoods and architects mostly linked in above tags to this post.]

The building (1968-70) just might be my personal favorite among commercial buildings in the Boston area. It was designed by Benjamin Thompson & Associates. The street level and a mezzanines above were designed as retail space for Design Research, a store for modern furnishings (importer of Marimekko, Danish furniture, Eames, Knoll, etc.) that Thompson had started in a nearby space in 1953. The building at 46 Brattle Street continues to house retail. From 1972-2009 it was a Crate & Barrel. Now it is an Anthropologie.

As explained in Heroic, a “fortuitous appearance of a salesman from Virginia Glass … led to the then-unprecedented use of butted glass without mullions, held with simple clips.” Thompson partner Tom Green recalls, “That frameless glass detail allowed D/R to be a building almost ‘without architecture’ …. it is “a deceptively simple package: concrete without brutalism, glass without glossiness, contextual without imitation.” *

The “contextual” refers to what became known as the “Architects’ Corner” in Cambridge. The Architects Collaborative (TAC) firm founded by Walter Gropius was the first to build at the corner of 46 Brattle and Story Streets. As a young founding partner, Thompson had been a motivating force to convince Gropius to form TAC. Thompson split from TAC to form his own firm, Benjamin Thompson & Associates (BTA) but remained in close contact with Gropius and the D/R building became the anchor for the corner. Indeed it was Thompson’s intent to design a solution to “turn corners and face the TAC building — and the constant effort to do something for the community scene — i.e. Brattle Street.” In 1970-71, Josep Lluís Sert, who succeeded Gropius at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, built the headquarters for his firm adjacent to D/R on Brattle. Earl Flansburgh, another one-time member of TAC built his own firm’s offices at One Story Street. Carl Koch, Hugh Stubbins, and Cambridge Seven Associates all had their practices nearby. Sert designed a significant amount of buildings in and around Harvard Square, including the Smith (formerly Holyoke) Center. And significantly the Carpenter Center, Le Corbusier’s only building in America, is located at Harvard.**

Le Corbusier was a pioneer in using concrete in commercial and residential building, attracted to its “plasticity,” among other traits. Which brings us to that off-putting term, Brutalism. Most of those familiar with the word believe it was coined to describe a school of design thought that resulted in the heavy concrete monumentalism seen in the ’60s-70s work of Paul Rudolph, Stubbins, Marcel Breuer, Kallman and McKinnell, and others. But the word originated from the translation of Le Corbusier’s french term betón brut, “raw concrete.” Reinforced concrete had been used at least as far back as the 1920s for more than just foundations, especially in Europe, where steel was expensive, particularly during World War II.

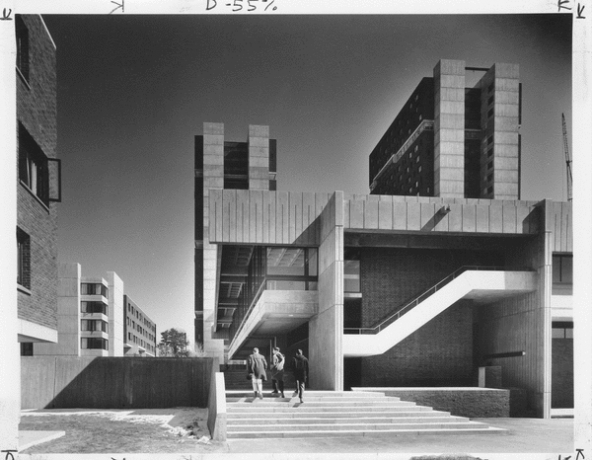

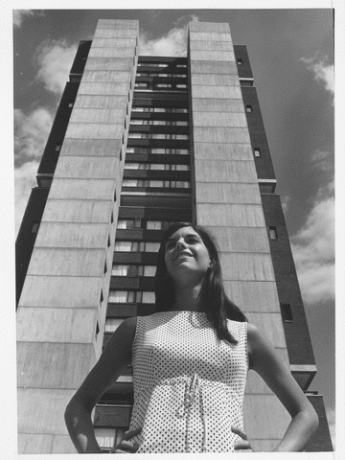

“New Brutalism” is a term that sprung up in the 1950s in England and “Brutalism” started to take a more specific meaning. The repetitive blocky modularity that many associate with concrete architecture, like that seen around Boston City Plaza by Rudolph and Kallman and McKinnell — and in Eastern Bloc countries — is what comes to mind. I went to the University of Massachusetts and lived for two years in just that sort of building, dorms designed by Stubbins in the Southwest residential area. We also had a striking Campus Center designed by Marcel Breuer and Associates and a Fine Arts Center designed by Eero Saarinen’s one-time associates Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo. And Rudolph, who like Stubbins started in lighter mid-century modernism, designed just that sort of “institutional” blockiness for much of the campus at UMass Dartmouth. Rudolph became the most famous practitioner of what we know as Brutalism, and the legacy of his buildings is not without controversy regarding preservation and renovation

Stubbins-Designed Buildings in Southwest Residential are of UMass Amherst

High Rise Tower in Southwest Residential Area

The authors of Heroic do a superb job of tracing the evolution of many modern architects of the ’50s-70s — by concentrating on the particularly fertile laboratory of Boston at the height of urban renewal policy — as they follow the lead of Le Corbusier and others. All of those who were interviewed reject the Brutalist descriptor and the authors themselves argue for “Heroic” as a replacement. According to the interviews in the book, none of them feels they were using the material in a philosophical way. The purpose was rationality. It was simply a material, one that was relatively inexpensive to work with. And it fit the context of the Boston surroundings, identified as it is with brick and granite masonry. So we have examples such as the relatively light touch of the D/R building at one end of the spectrum, and the imposing monumentality of Boston City Hall and City Hall Plaza on the other. In addition to that plasticity that attracted Le Corbusier, architects were compelled by the “honesty” of “monolithic” concrete. During this era, concrete was used as the structure and the finish of the buildings, a unified system where it was the through-line from foundation, through the flooring and ceiling slabs, exterior and interior walls, roof, and to the interior and exterior finish. Designers generally did not add wall board or dropped ceilings to allow for the hiding of systems. HVAC and electric lines (in metal or plastic channels) were left exposed. There was usually not any other exterior skin or other facade. In some cases, the designers would leave the exterior raw and others would polish and smooth the finish.

Concrete as such a unifying material was almost exclusively used for public, commercial, or apartment buildings. Almost, for as we get to the end of the book, there is a study of the work of Marty Otis Stevens and her one-time partner and husband, Thomas McNulty, who built a concrete house for themselves in Lincoln on Weston Road along Beaver Pond in 1965, as well as a series of others on commission in nearby towns.

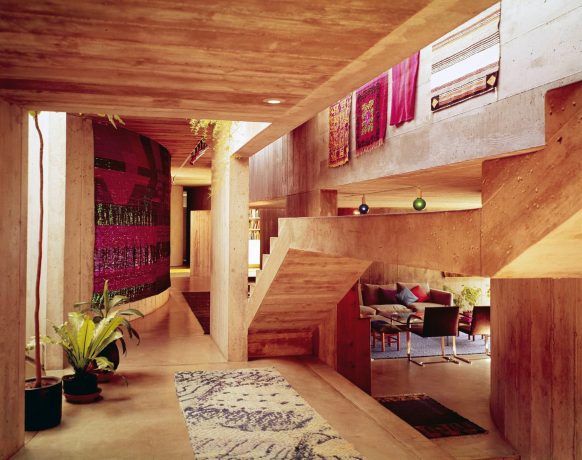

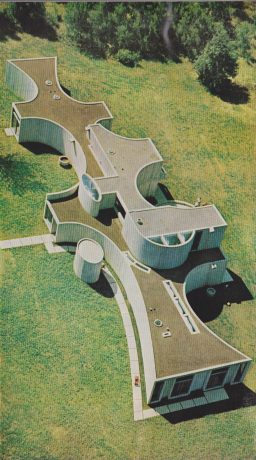

In contrast to the architects of the commercial buildings, concrete was elemental in underpinning an overall philosophy behind the design McNulty and Stevens had for their own home. They were, according to Heroic, setting themselves in opposition even “to the more conventional examples of postwar suburban modernism by other architects nearby, such as Six Moon Hill by the Architects Collaborative.” There were no interior doors in the Lincoln House and Studio. A system of free-standing curvilinear walls provided the relatively small amount of privacy compared to traditional layouts. And their shared studio was part of the design. “A family can be imagines as a nucleus of movement,” they pair wrote, in which participants might “move at random, self-driven by the free forces of inner development, interest, and singular abilities.” As quoted in Heroic, “They wrote that in a truly modern living arrangement, ‘The spatial continuity between environmental functions implies that one would be absolutely free to develop a scope and sequence of activities by the day, lifetime, year — the increments of time, like the uses of space, being individual determinations.'”

Heady stuff, consistent with, for example, Montessori or Waldorf School theories on education. Reflecting back in 2000, Stevens, one of few women architects in the ’60s, explained, “I was against ordinary domesticity. I didn’t want my children to grow up in the conventional restrictive environment in which I had been brought up.” Instead, Heroic notes via a quote from a 1965 edition of Architectural Forum, the “uninterrupted volume” is “a single meandering space 150 ft. long, enclosed by swirling walls of fine-textured, lightweight concrete.”

Photos of the Lincoln House by Julius Shulman

The couple lived and worked in the house for 13 years, at which point it passed on to renowned opera conductor Sarah Caldwell. Sadly, the Lincoln House and Studio was torn down without a permit in 1999. According to the book Impossible to Hold: Women and Culture in the 1960s, “only afterward did the town require permits for tearing buildings down.” McNulty and Stevens designed three other concrete homes, one of which was never built. The Cabot House in Manchester, MA has been, according to the authors, “disfigured with unsympathetic additions, while the Torf House in Weston alone remains under original ownership.