SOLD. Click any photo to enlarge and watch as slide show. Photos by Lara Kimmerer except as noted.

- North Elevation

- Entry

- Living Room

- Foggy View

- Living Room

- Recently Updated Eat-In Kitchen

- Kitchen

- Recently Updated Bath

- Master Suite with Full Bath and Dressing Room

- Detail

- Study

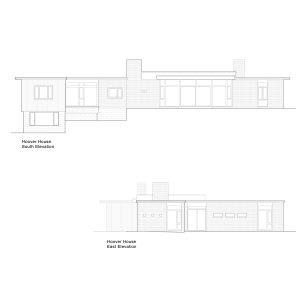

- South Elevation

- View – by Bill Janovitz

- Detail –by Bill Janovitz

- Elevation

- Elevation

The house is always its site.

This was the operating principle of the earliest Modernist architect in Lincoln, Henry B. Hoover, who in 1934, climbed this hill overlooking the Cambridge Reservoir and paid $1,000 for two acres on which to build a house for his family. In 1935, he sketched out the house that would be completed in 1937, predating Lincoln’s more famous Gropius House by more than a year. Walter Gropius, who after co-founding the Bauhaus in Dessau, fled Nazi Germany to take the chairmanship of the Department of Architecture at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design in 1936. Gropius’ reputation preceded him, but Hoover had already been working on Modernist ideas before the arrival of the renowned German. Hoover ended up designing over 25 other houses built in Lincoln and close to 100 residences overall.

Like Gropius, Hoover was a transplant to New England. Raised in Idaho, he studied at the University of Washington as an undergraduate, and then went on to Harvard for his degree in architecture. After a fellowship that allowed him to travel in Europe, he first went to work for Fletcher Steele, a celebrated landscape architect of the 1920s and 1930s. These two tracks of his training are seen converging in his work, beginning here at his own house at 154 Trapelo Road. As described in the upcoming book about his work, Breaking Ground: Henry B. Hoover, New England Modern Architect, “Hoover’s practice demonstrates how he utilized, transformed, and individualized prevailing Beaux-Arts architectural training of the 1920s to achieve a modern residential architecture informed by—but different from—the normative (Bauhaus driven) idea of modern architecture.” In the Ecole Beaux-Arts tradition, students take a position, a stance, a decision, called a PARTI’. Hoover’s PARTI’ is that a house is always its site.

This prevailing philosophy is made abundantly clear here at the Hoover House. As with most of his subsequent designs, the architect’s design guides visitors through a series of phases of revelation. With 154 Trapelo Road, you turn off the main road, up a narrow private country lane that gently ascends toward the site. Turning into the pebble driveway, you leave the car and walk up some steps on the north side of the house. Entering the foyer, there are some more steps up into the house, where you turn to the right into the south-facing central living area and are dramatically presented with the view. Neither words nor pictures can replicate the experience that unfolds as you enter. The breathtaking vista over the Cambridge Reservoir draws you in and almost back out, onto the south side, through the wall of windows to the flagstone terrace and rocky terrain beyond, as it gently slopes back down in the direction of the water. Hoover is like a master dramatist, setting the stage for you. (You can see some video below.)

For his children, Lucretia Giese and Henry B. “Harry” Hoover Jr., growing up in the house meant enjoying this view during every season. The original eight-room house had smaller panes of glass, a higher ceiling, and a darker wall on the fireplace side. In 1955, the house was remodeled and expanded and Hoover was able to take advantage of new materials, such as large sheets of glass. He lowered the ceiling and lightened the wall, while also adding a new wing with two bedrooms and a bath on the west side of the house. The original house had two bedrooms and one bath, which were changed into a master suite with a full bath and dressing room. Radiant floor heat was also added in the 1955 remodel, and it still functions today, though there is also a 2004 hyrdo-air system with central air conditioning, a high-efficiency Munchkin boiler, and a Superstore passive hot water storage tank. The heating is fueled natural gas, a rarity in Lincoln. This also allows for gas cooking on the Bosch countertop range in a kitchen recently renovated, along with one of the bathrooms, under the enlightened and informed care of architect Gary Wolf. Thermopane windows were added circa-2000. There is a rubber membrane roof.

Similar to other Modernists, Hoover designed the house so that there was a private corner with the bedrooms, another side with the kitchen and utility areas, and used most of the space — the central core — for the living areas where the family could congregate. As with the Earl Flansburgh House, designed and built in Lincoln decades later, there is a study on the other side of the living room fireplace, also with its own fireplace. This allowed for the family to observe their father’s comings-and-goings and his work processes with a certain degree of transparency.

As the house is the site, Hoover spent much time outside, placing as much importance on the outdoor spaces as the indoors. In the documentary film with the same name as the forthcoming book (written and directed by Molly Bedell), Harry Hoover recalled that he worked the land “as a sculptor would model clay,” with thoughtful plantings and even lugging rocks around the property, hand building the stone walls that remain standing today. Harry points out that Hoover’s designs are asymmetrical, following the topography, sited as naturally “as a rock and a tree.” The exterior was clad in second-hand brick and is whitewashed and weathered as per the architect’s original plan. Each of Hoover’s houses was individually designed with the needs of each client in mind, harmonizing problem solving, the needs of the family, and the opportunities of the site. He even custom designed pieces of furniture for the houses, and the Hoover House contains some of those, including the dining room table and a serving buffet that is built into the wall nearby. His timeless design offers a space for everything and they are works of art.

Though most of his designs were for small modern houses, his clients tended to live in them for the rest of their lives, in some cases modifying as needed. As quoted in a recent article in Harvard Magazine, Lucretia Giese noted that the house, reflects her father’s “foremost concern with siting and spatial organization, which accentuated the house’s integration with the land. Overlooking the Cambridge Reservoir, the house remains eminently livable and beautiful.”

Preservation

When Hoover first had the vision of his house for the site at 154 Trapelo Road, it took a bit of convincing to get his lenders to approve financing. They had only seen flat roofs on filling stations, just as the bankers in Lexington took to referring to the TAC houses of Six Moon Hill and Five Fields as “those chicken coops.” Appreciation of Modern houses has certainly come a long way, thanks to such preservation groups as DOCOMOMO, FoMA Lincoln, and Historic New England. And frankly, with these houses standing the test of time, market forces and changing demographics in the Boston area have contributed to a general appreciation of Modern architecture. Perhaps these economic trends are the most important factors in the preservation of such houses, as formal preservationists face an uphill battle if no one wants to live in the houses they are charged with protecting from demolition.

However, given the modest size on the outstanding site of the Hoover House, without formal preservation guidelines, there would be the very real threat of some Master of the Universe taking it down in order to build some sprawling trophy home overlooking with this view and location, minutes off of Route 128 and so close to Boston and Cambridge. Indeed some of the 50-plus Hoover-designed houses have been demolished. One, the Heck House in the center of Lincoln, in the Historic District, was saved from the wrecking ball in 2006. On a fantastic six-acre site atop a heartbreak hill for cyclists, Hoover had transformed a Victorian into a Modern house in 1948. As noted in the New York Times in 2011:

Mr. Hoover’s son, Henry Hoover Jr., said he had seen several modern homes torn down and wanted to protect theirs from people who might consider modernism “a Johnny-come-lately” and want to build something else on the two-acre lot once he and his surviving sister, Lucretia Giese, are gone.

“Modernism is loved in some quarters but not others,” Ms. Giese said as she showed a visitor around the compact brick and wood house on a hill, with plate-glass windows looking out on a rocky landscape. “People are less willing to adapt their own needs to what’s there.”

You may have also noticed that the Hoover House was the Boston Globe’s pick for Home of the Week on Memorial Day Weekend.

The Historic New England Stewardship Program

Because our father designed the first modern residence in Lincoln, we have long felt a responsibility to preserve its essential character. The stewardship program of Historic New England, which combines private ownership with easements, offers the assurance of protection in perpetuity that we wanted.

— Lucretia Hoover Giese and Henry B. Hoover Jr. June 2015

In 2008, The Hoover House became the first modern house become part of the Stewardship Program of Historic New England. This is a program that allows houses to live on with new owners without becoming museums owned by the organization. An example of the latter would be the Gropius House. The most recent and applicable example of a local house in the Stewardship Program would be the Flansburgh House, which we listed last year for $1,050,000 and sold for $1,167,000. In order to protect the house and the legacy of Henry B. Hoover, Hoover’s three children worked with Historic New England to establish a preservation easement to ensure that the house will not be demolished, neglected, or altered insensitively. Owners of the house will not need to make the house open to the public and will be able to make changes to the house, including finishing the basement, updating systems, upgrading kitchen appliances, and other actions that will not significantly alter the setting and original design of the house. Owners have the ability to decorate the interior of the home with furniture, artwork, and carpeting of their choice.

Historic New England stands ready to serve as an invaluable resource in this regard. Joe Cornish, from the organization, notes, “The goal of the preservation easement is to preserve the unique setting and character of this significant and intact example of mid-century Modern architectural while making it adaptable for modern living.” Joe will be available at two of our open houses (Saturday and Sunday) to chat with potential buyers. We also can provide the documents pertaining to the easement upon request to those who are considering submitting an offer.

Dwell magazine covered the Stewardship Program and featured the Hoover House in 2012. In that article, Jess Phelps, Team Leader for Historic Preservation at Historic New England, pointed out, “Easements do prevent insensitive alterations or teardowns from occurring, but aren’t designed to prevent houses from adjusting to contemporary use—they are actually designed to facilitate this transition—albeit in a sensitive fashion. For example, Historic New England typically doesn’t restrict bathrooms and kitchens as these areas do evolve so much over time.”

For a general FAQ about the Stewardship Program, see this link.

Thanks to Machine Age for lending us some furniture — two Alvar Aalto chairs — for the staging.

Details

Offered at $1.1 million. Open houses:

Friday, June 5 from 4:00-6:00

Saturday, June 6 from 1:00-3:00

Sunday, June 7 from 1:00-3:00

Any/all offers shall be reviewed Tuesday, June 9 at 3:00.

Contact us to set up a private showing and for any questions, including a request for the preservation easement.

- 2,879 s.f. on Lincoln public record field card.

- Three bedrooms.

- Two full baths.

- 100,168 s.f. lot (2.3 acres).

- Private road/drive from Trapelo shared by other homeowners and cost of snow removal is split among them. But each house has its own driveway.

- Bosh and Fisher/Paykel kitchen appliances.

- Bosh washer and dryer included.

- Updated electric with circuit breaker panel.

- Radiant floor heat.

- Second heating and AC system installed in 2014.

- 2004 Superstore passive hot water storage tank.

- Town water.

- Private septic replaced with new within past 15 years.

- Two-car carport.

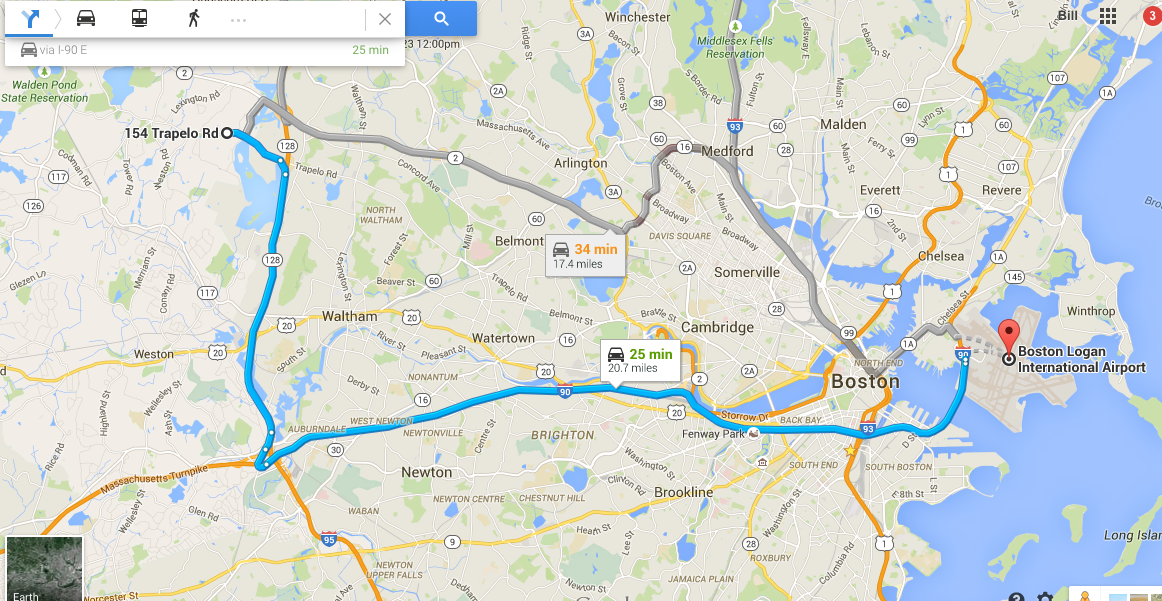

- 25 minutes to Logan Airport:

Here are some Instagram clips we took of the entrance and view:

Entering the Hoover House, 1936/37. First Modernist house in Lincoln MA. Check the view over the Cambridge Reservoir. We will have it listed in a week or so. Read about it at the Boston Globe site, linked at modernmass.com A video posted by Bill Janovitz (@billjanovitz) on

Hoover House 2 A video posted by Bill Janovitz (@billjanovitz) on