Click any photo, and click again to enlarge:

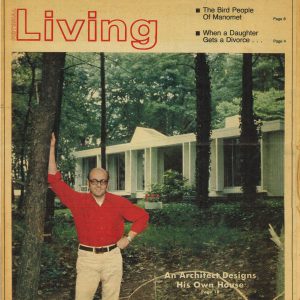

- Earl Flansburgh in front of his family’s house in Lincoln

- Entry

- Living room

- Curved closet and dining room

- Light switches and nightlight

- Custom-designed desk for bedroom

- Eames Lounge Chair in study

- Custom-designed shelving by Earl Flansburgh

- Study desk

- Hallway along playroom

- “James Bond Tunnel” to garage

- Study

Photos by Lara Kimmerer (except for the vintage newspaper shot).

“Architecture should be exciting; living is exciting.”

Earl Flansburgh

Nestled up on a knoll in the pines of Lincoln, on a lot peppered with colorful sculptures (see list at end of post), the Modernist Flansburgh House epitomizes the mid-century movement of Modernists to “the woods” of the Boston area.

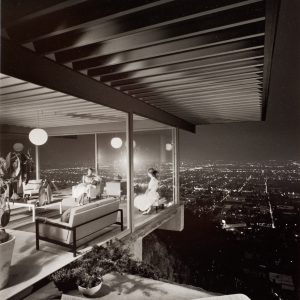

The optimism inherent in Mid-Century-Modern architecture is perfectly at home in the sunny climates of the West Coast and Southwestern United States, but to many observers, such houses come as a surprise in the Boston area. Seeing a Neutra house cantilevered over the Hollywood Hills might at first seem more natural than, say, turning the corner in an old New England town and seeing a striking, white, flat-roofed house, peeking out from behind oaks and firs. But such a dramatic juxtaposition, as seen with the Flansburgh House, is in fact perfectly simpatico with its surroundings, consistent with principles of such New England forebears as Emerson and Thoreau, in harmony with nature. Indeed, the thoughtful siting — designed and built in 1963 to work with the terrain and upset the land as little as possible — is far less imposing than most of the region’s more recent construction. As with most of the homes featured on Modernmass.com, the Flansburgh House is proof that at one time, optimism and an international worldview were common enough — and land inexpensive enough – in the Boston area to allow for such pioneering design to flourish. With appreciation for the Modernist design of the mid-century on the rise in this increasingly diverse and world-facing region, we see a hopeful renaissance of the optimism that fueled the post-war era.

Earl Flansburgh received his Masters Degree in Architecture from MIT in 1954 and spent some time in the UK on a Fulbright Scholarship. When he returned to the Boston area, he worked for a few years with The Architects Collaborative (TAC), before forming his own firm, Earl R. Flansburgh + Associates (ERF + A) in 1963. He practiced architecture in the Boston area for more than 45 years, focusing on planning and design of educational facilities. Flansburgh Architects Inc. (FAI) still bears his name.

The Flansbugh house was completed in 1963, designed for the architect’s family. The two boys were three and six at the time. Schuyler is now an environmentalist living in Virginia and John is one half of the beloved They Might Be Giants. John briefly discusses growing up in the house here. Designed around an interior garden courtyard, which the architect said, “brings nature in on our terms,” natural light spills in from the walls of windows that surround the courtyard, as well as skylights and large windows in the rear of the house.

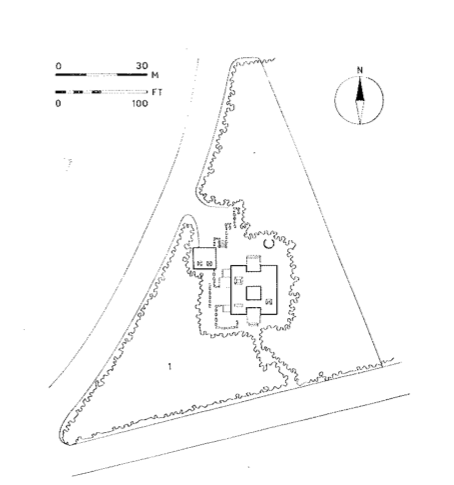

- Sketch of the siting

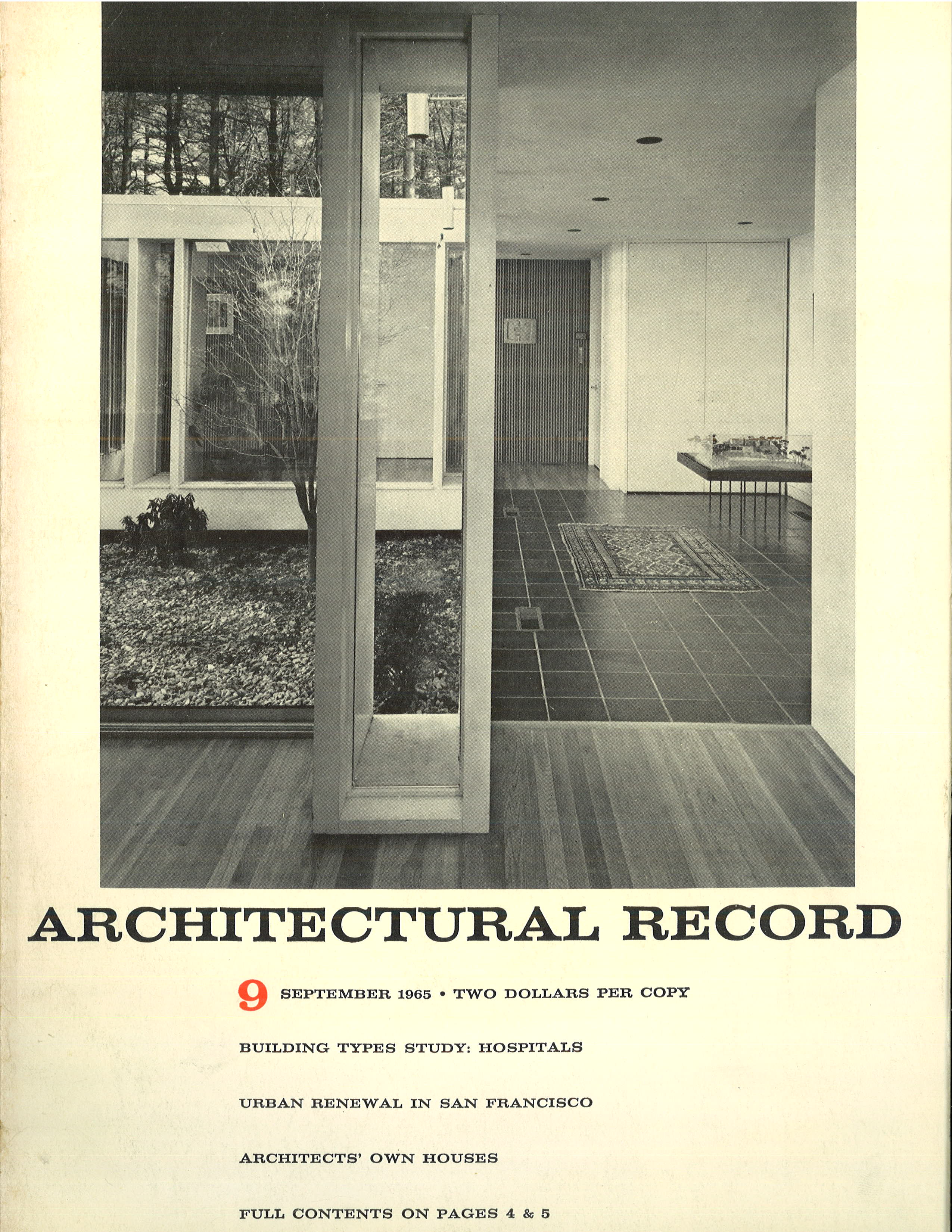

Sited on a triangular lot in between Conant and Old Conant Roads, there are welcoming entrances from both roads. The formal entrance has a foyer overlooking the courtyard, and a coat closet. After his wife, Polly (founder of Boston By Foot) beseeched him, Flansburgh designed a two-car garage that is attached to the basement via (in John Flansburgh’s description) a “secret James Bond tunnel.” It was added in 1967. The house was featured in Better Homes and Gardens in 1966 and as a cover story in Architectural Record in 1965.

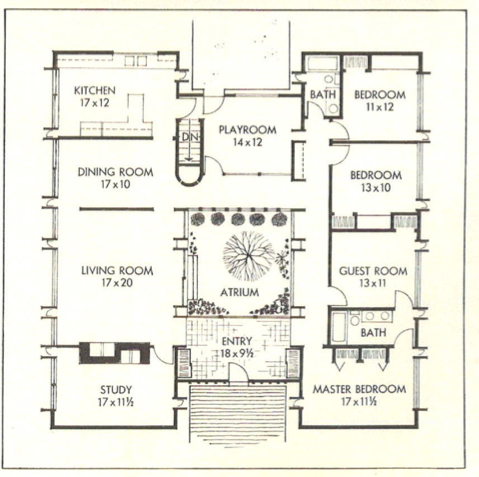

- Floor plan as shown in 1966 Better Homes and Gardens.

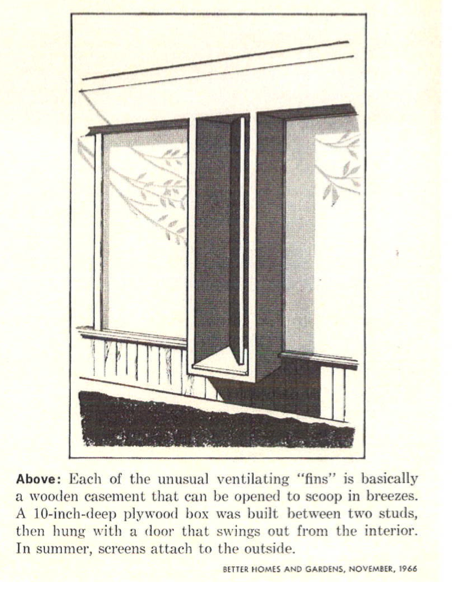

Each room just feels right. Laid out on one floor that makes a rectangle around the courtyard, there are four bedrooms, two full baths, a formal dining room, the kitchen, a study, and a “playroom,” which could also work as a studio, office, etc. Floor-to-ceiling windows and glass sliding doors in the living room face the courtyard on one side, while large windows flank the side facing the road. The facades also have vertical “fins,” painted in Mondrian-like sunny yellow, which operate as ventilation and, when opened in conjunction with the sliders to the courtyard, produce air flow that circulates through the entirety of the house no matter which direction the breezes may blow.

- A detail taken from a 1966 Better Homes and Gardens feature on the house.

It is as much about these sorts of details as it about the overall impression one gets when visiting that makes the house so special. Two custom-designed fireplaces — one in the living room, the other just beside it in the study — have simple-yet-ingenius built-in risers that eliminate the need for sets of andirons. In the playroom, a retractable wall of cork board accordions open and closed. A curved slatted wall opens to reveal a broom closet.

The house is beloved in Lincoln and was featured in a tour with FoMA (Friends of Modern Architecture) Lincoln.

Preservation

NYT Photo of Polly Flansburgh by Gretchen Ert

In order to protect the house and the legacy of Earl Flansburgh, Polly Flansburgh worked with Historic New England to establish a preservation easement to ensure that the house will not be demolished, neglected, or altered insensitively. Owners of the house will not need to make the house open to the public and will be able to make changes to the house, including finishing the basement, adding air conditioning, changing windows, making kitchen upgrades, and other actions that will not significantly alter the original design of the house. Dwell magazine covered the Stewardship Program and featured the Flansburgh House in 2012. In that article, Jess Phelps, Team Leader for Historic Preservation at Historic New England, pointed out, “Easements do prevent insensitive alterations or teardowns from occurring, but aren’t designed to prevent houses from adjusting to contemporary use—they are actually designed to facilitate this transition—albeit in a sensitive fashion. For example, Historic New England typically doesn’t restrict bathrooms and kitchens as these areas do evolve so much over time.”

“For me this program has been an answer to a question Earl and I both had about what to do with the house,” Polly Flansburgh told Wickedlocallincolnnews.com. “Once our children moved away from Lincoln and began their lives in other places, we were presented with a conundrum. To think that generations are now going to be enjoying this house is thrilling. Earl would be pleased.”

For a general FAQ about the Stewardship Program, see this link.

Other sources not linked: Obituary; Architect Built Homes Photos and Article: Caitlin Corkins, Stewardship Manager Historic New England.